Seeking information about the anus and anal cancer can feel overwhelming or frightening, especially if you’re unsure about what’s ahead for you or a loved one. Having the right information can help lessen some of these feelings. Here you will find reliable information about the anus and anal cancer along with diagnosis, symptoms, risks, treatment, side effects, diet and nutrition and some useful websites to visit.

Nau mai rā, rarau mai rā ki tēnei whārangi mō ngā kōrero e pā ana ki te mate pukupuku kōtore.

About the anus

Mō te kōtore

The anus is the opening at the end of the large intestine and is an important part of the digestive system.

Click here to learn more about the structure and function of the anus.

The opening at the end of the large intestine where stool (bodily waste/poo) leaves the body, is called the anus.

Just above the anus is the anal canal which is about 4cm long and is connected to the rectum where stool is stored.

Surrounding the anal canal are two layers of ring-like muscles called the internal sphincter and external sphincter. When the internal sphincter relaxes, stool moves from the rectum into the anal canal. When the external sphincter relaxes, stool moves out of the body.

The anal canal is lined by moist cells called the mucus membrane. The mucus membrane has glands that release moisture to soften stool and allow it to pass out of the body easily.

The lower part of the anal canal and the skin surrounding the outside of the anus (perianal skin) is lined by cells that are similar to skin cells called squamous cells.

Click here to see a diagram of the rectum, anal canal and anus | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei mō te hoahoa tōngātiko, ara kōtore, kōtore

What is anal cancer? | He aha tēnei mea te mate pukupuku kōtore?

Anal cancer occurs when abnormal cells grow out of control.

75% of all anal cancers start in squamous cells which line the anal canal and opening of the anus. This is called squamous cell carcinoma of the anus.

Other types of anal cancer have different names depending on where they are and what cells are involved. These can include:

adenocarcinoma (Paget’s disease)

basal cell carcinoma

mucosal melanoma

gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST); and

karposi’s sarcom.

Sometimes cells of the anus are pre-cancerous, meaning that they are not cancerous yet, but they could turn cancerous if not treated. This is called anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN).

Anal cancer statistics in New Zealand | Ngā tauanga mate pukupuku kōtore i Aotearoa

Anal cancer is a very rare form of cancer and is usually treatable with radiotherapy. Living with a rare form of cancer can be distressing - you might feel alone or isolated with what you’re dealing with. There can also be stigma or feelings of embarrassment knowing that you are affected by anal cancer. Although uncomfortable, these feelings are quite common. Overcoming these by challenging your own thoughts or perceptions about anal cancer and connecting with others in the same situation as you can help.

You can learn techniques to manage any cancer-related distress on our Living with Cancer pages.

Ask your medical team or the Gut Cancer Foundation about linking you to patients or carers in the same situation as you, if you feel this would make a difference for you.

Click here to learn more about anal cancer statistics in New Zealand

Over a 5-year average, 4.98 people for every 100,000 people are diagnosed with anal cancer.

Cancer is most common in those over the age of 70.

Symptoms & Risks

Tohumate & Tūraru

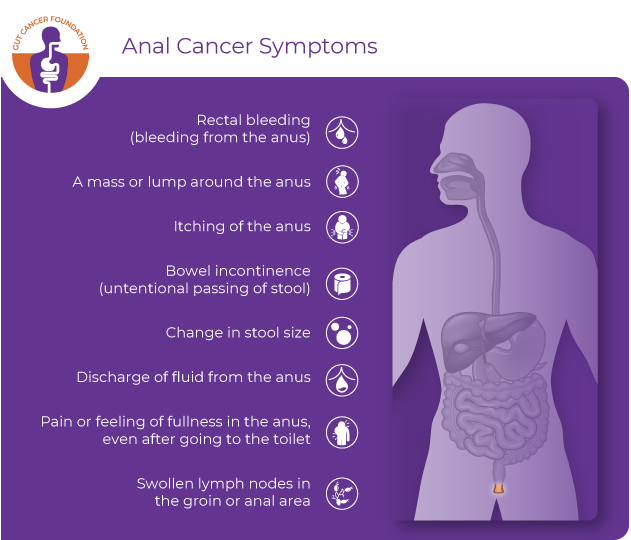

Symptoms of anal cancer | Ngā tohumate o te mate pukupuku kōtore

Anal cancer may not cause any symptoms, or if there are symptoms, they are often similar to other conditions such as haemorrhoids or anal warts.

It is important to note that having one or more of these symptoms does not necessarily mean that you have cancer, but if you have new or persistent symptoms that are out of the ordinary for you, it’s really important that you contact your GP to get checked out.

Click here to view symptoms of anal cancer | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei kia tirohia ngā tohumate o te mate pukupuku kōtore.

It is best to see your doctor for review and investigation if you experience unexplained symptoms that worry you. They will ask you questions to help understand whether the cause of symptoms is anal cancer or another condition.

Managing symptoms | Whakahaere i ngā tohumate

You may notice that things change for you physically and emotionally following your diagnosis and you may have even noticed some of these symptoms prior to diagnosis. Understanding them can help you to prepare for them mentally and manage them if they do appear. If you do experience any of these symptoms, let your healthcare team know when you next see them. If they are extreme, or you are worried about them, get in touch with your healthcare team sooner.

Click on the links below to learn about some ways you can manage these changes or symptoms | Pāwhirihia te momo tohumate mō ētahi atu mōhiohio.

Changes in diet | Ngā panonitanga o te whiringa Kai

Many people find that sorting out symptoms related to their diet makes the biggest difference to how they feel. Ask your doctor or nurse for a referral to a dietitian. They can help you with finding food to eat that is gentle on your digestive system.

Nausea | Whakapairuaki

Feeling sick (nauseous) is another common symptom. You may be prescribed anti-sickness medication, or you could try home remedies such as ginger, peppermint, or acupressure bracelets.

Fatigue | Ruha

You are bound to feel tired or exhausted sometimes, so be kind to yourself. Make sure you rest and prioritise what you want or need to do. Give yourself permission to accept offers of help for chores that feel overwhelming. Although you might not feel like it, gentle exercise such as stretching, or a short walk can help combat fatigue.

Intimacy | Mateoha

People of all genders can lose interest in sexual activity during cancer treatment, at least for a time. Although it can feel awkward, talking to your partner about what you find intimate, or soothing can help. There are many ways to be intimate, such as cuddling or gentle touch, or using warmth and comforting language. Your GP may be able to assist with medication or a referral to see a sex and relationship therapist.

Stress, pain, and anxiety | Kohuki, Mamae, Anipā

Simple relaxation techniques can help you cope with stress, pain, and anxiety. Having a warm bath, deep breathing or listening to soothing music are easy things to do at home. You might want to try complementary therapies like reflexology or aromatherapy massage. Talking to others can also help. There are many cancer-specific psychologists available to you in New Zealand – ask your oncologist, nurse, or GP for a referral.

Keep perspective | Kia whakataurite

Each individual will feel and react differently to treatment. What might work for someone else may not always work for you. Acknowledge that not every day will be as easy to manage as the last, and that every day may be different. Focus on what you know works for you and be very gentle with yourself.

Keeping active | Kia kori

Physical activity can also make you feel better, though how much activity will depend on how well you feel. Even a walk round the block or 10 minutes of stretching each day can help.

Risks of developing anal cancer | Ngā tūraru whakawhanake mate pukupuku kōtore

There are some known risk factors that can increase the chance of anal cancer developing. Having a risk factor does not automatically mean that you will develop anal cancer, but they do increase the likelihood of it happening.

Knowing your risk factors and talking about them with your doctor may help you make more informed lifestyle and health care choices.

Some risk factors are environmental and within your control which is why it is important to understand what they are.

Risk factors | Ngā pūtake tūraru

HPV (human papillomavirus) infection

receiving anal sex and having many sexual partners

having a weakened immune system – for example:

if you are taking immunosuppressants

if you have a disease (such as coeliac disease, lupus, or Graves’ disease) or a virus (such as human immunodeficiency virus - HIV) that weakens the immune system

history of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer

smoking tobacco

age – the risk of anal cancer increases with age especially after the age of 50.

Diagnosis

Tautohunga

Diagnosing anal cancer | Te tautohunga i te mate pukupuku kōtore

Being diagnosed with cancer can be a scary time for anyone. Here you will find information to help you understand some of the terms you might have heard.

In order to diagnose anal cancer, your oncology specialist will do a range of tests. There might be one test or a mix of tests, some of which are explained below.

Blood Tests | Whakamātau toto

Your doctor will usually take some blood to test first. These blood tests can check to see if:

your red blood cell count is low. Bleeding as a result of anal cancer can cause anaemia

your white blood cell count is high. This may suggest that your body is fighting unwanted changes, such as cancer cells, in your body

yhere are any changes in your liver and kidney function.

Physical examination | Whakamātautau tinana

Your doctor may need to examine you by performing a digital rectal examination. This is where the doctor will put on medical gloves, lubricating one of the fingers, and insert their finger into your rectum to feel for any abnormalities such as lumps.

Endoscopy | Tiro oranga whēkau

An endoscope is where a flexible tube with a camera and light on the end is placed into the anus so that the doctor can examine the inside of your body. There are three different types of endoscope that may be used.

anoscope – to examine the anal canal and end of the rectum

proctoscope – to examine the rectum

sigmoidscope – to examine the rectum and end of the colon.

The endoscope will allow the doctor to see if there are any changes or lumps, and if there has been any bleeding, if it is coming from the anal canal or rectum.

Click here to see a diagram of an endoscopy

Biopsy | Tīpako pūtautau

A biopsy is where a small amount of tissue is taken for testing in a lab to see if there is cancer present in any polyps or lumps in the anal canal or rectum. A biopsy can be done at the same time as the endoscopy. If cancer is present, the biopsy can also help to determine what stage the cancer is at.

The biopsy is usually done in an outpatient clinic. The biopsy may be uncomfortable but should not be painful. Following the procedure, you may experience a little bleeding and soreness which should subside within a few days.

Click here for a diagram of a biopsy.

Fine Needle Aspiration | Tīpako pūtautau ā ngira rauiti

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) is where a very thin needle with a syringe is inserted through the skin and into lymph nodes in the groin. A small amount of fluid is taken to see if there is any cancer present in the lymph nodes.

FNA is often done in an outpatient setting. You will be lying down and may be given a local anaesthetic to numb the area where the needle passes through the skin. A CT scan may also be used to help the doctor guide the needle into the correct place.

Sometimes more than one FNA may need to be taken on the day, in which case a new needle will be used each time. The procedure can be uncomfortable and may cause slight bleeding where the needle entered the skin but is not usually painful and the bleeding is managed with a bandage.

Although the area is cleaned prior to the FNA as with any procedure that pierces the skin, there is always a risk of infection.

Transrectal Ultrasound (TRUS) | Oro ikeike o te ara kōtore

A transrectal ultrasound is when sound waves are used to make an image of the inside of the anal canal and rectum.

An ultrasound transducer (probe), which is about the width of a finger, is inserted into the anus and is able to tell the doctor the stage of the cancer and if the cancer has spread to the vagina (in women) or prostrate (in men). The test usually occurs in an outpatient setting and takes about 10-15 minutes. You will usually be asked to lie on your side with your knees curled up into your chest. You will normally be given an enema 1-4 hours before the TRUS to clear out the bowels.

Computed tomography (CT) scan | Matawaitanga-ā-rorohiko

A computerised tomography scan (CT scan) is used to see if cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes, or other organs in the pelvis, abdomen and chest.

A CT scan combines a series of x-ray images that are taken from different angles around the body. You will lie on a motorised bed that passes through a doughnut shaped tube. It is important that you lay still for good quality images to be taken and so a strap and/or pillows may be used to help with this. It isn’t painful and usually takes about 1 hour in an outpatient setting.

to prepare for the scan, you may be asked to | Hei whakarite i mua i te whakaata roto ka pātaihia pea i ēnei pātai:

stop eating or drinking for 4 hours before your scan

take off some or all of your clothing and wear a hospital gown for the scan

remove all objects such as jewellery, piercings, dentures and glasses as they will interfere with the picture quality.

A CT scan uses small amounts of radiation. This is greater than the amount you would get during a simple x-ray, however it is still a small amount and so the risk to your health is very low. The low dose of radiation you are exposed to during a CT scan has not been shown to cause harm.

Click here for an example of a CT Scan.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Whakaahua ponguru autō

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) is used to check if cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or other organs in the pelvis and abdomen.

An MRI scan uses magnet fields and radio waves to produce a detailed picture of the body. You will lie on a bed that moves into a tube. It is important that you lay still for good quality images to be taken. It isn’t painful and usually takes between 15 and 90 minutes in an outpatient setting. An MRI scan is very noisy and so you may be given headphones to wear. For those who do not like small spaces it may cause some anxiety. If this is the case, speak to your doctor before your MRI as they may be able to provide you with some medicine to help you feel calmer. The MRI technician will be used to people feeling anxious, so don’t hesitate to speak up if you need more support once you get there. Deep breathing and focusing on calming scenes while you’re in the MRI can also help lessen anxiety.

To prepare for the scan | Hei whakarite i mua i te whakaata roto:

you may be asked to stop eating a few hours before the scan, but your medical team will let you know if this is required.

you may need to take off some or all of your clothing and wear a hospital gown for the scan

you will need to remove all metal objects such as hair clips and piercings - and possibly medical patches if you wear one - as they may contain metal.

It is important to tell the radiology staff about any metal you have in your body including possible metal fragments, such as in your eye. Objects that have been implanted in your body need to be discussed ahead of the MRI scan as they may cause harm or be damaged. These include pacemakers, aneurysm clips, heart valve replacements, neurostimulators, cochlear implants, magnetic dental implants and drug infusion pumps.

Click here to for an example of an MRI Scan

Chest X-Rays | Hihi tiro Poho

Chest x-Rays are used to check if anal cancer has spread to the lungs.

Chest x-rays use small doses of radiation to take an image of your lungs. These are usually undertaken in an outpatient setting and take about 10-15 minutes. The test is not painful, and you can go home afterwards.

Click here for an example of a chest x-ray

Positron emission tomography (PET) | Matawaitanga-ā-rorohiko whakarau pūngao

A PET scan can be used to help diagnose anal cancer and determine the stage of the cancer. It can also see if the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes or other organs in the pelvis, abdomen, or chest. The scan may be used by doctors prior to surgery to plan the procedure.

A PET scan uses a special type of camera that detects radioactive material. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into your arm about 1 hour before the scan which will travel and accumulate in areas of the body where there is higher metabolic activity i.e., where there is disease occurring. The body is then scanned to show where the radioactive material is accumulating.

Similar to the CT scan, you will lie on a motorised bed that passes through a doughnut shaped tube. Sometimes the CT scan and PET scan are combined in the same machine and both types of images are taken at the same time.

It is important that you lay still on the bed for good quality images to be taken and so a strap and/or pillows may be used to help with this. It isn’t painful and the whole procedure usually takes about 2 hours in an outpatient setting. Allergic reactions can occur due fto the radioactive material but are extremely rare. After the procedure you naturally pass the radioactive material out of your body in your urine.

To prepare for the scan you may be asked to: | Hei whakarite i mua i te whakaata roto ka pātaihia pea i ēnei pātai:

Avoid strenuous exercise for a couple of days beforehand

Stop eating 4 hours before your scan.

Click here for an example of a PET scan. *Source: Mediplus.in

It's important to acknowledge that some of these tests can be confronting or sometimes frightening. Taking a friend or whānau member with you can help ease anxiety. Be encouraged to tell staff if you need extra reassurance during the test, you'll find some very compassionate people working in healthcare.

Waiting to have tests carried out | E tāria ana kia whakamātauhia

Even if you have been given an urgent referral for a particular scan or investigation you may have to wait several days or possibly weeks for your appointment. This can be frustrating and worrying, especially if you are already feeling unwell.

Several weeks of testing to confirm a diagnosis or awaiting appointments is relatively common and is unlikely to alter overall outcomes. Cancer growth is considered to be negligible over a period of weeks, and this waiting period is unlikely to cause you harm if your symptoms are stable.

If your symptoms get worse or you start to feel more unwell while you are waiting, it is a good idea to get in touch with your GP or specialist if you already have one. If you cannot get in contact with them, you may need to present to the closest emergency department if your symptoms cannot be controlled at home.

How long will I have to wait for my test results | Ka hia te roa e tatari ai kia puta ngā kitenga whakamātautau?

Depending on which tests you have had it may take from a few days to a few weeks for the results to come through. Waiting for test results can be an anxious time.

It is a good idea to ask how long you may have to wait when you go for tests. If you think you have been waiting too long, then contact your GP or a specialist to follow up on the progress of your results. Usually, the doctor who does the test will write a report and send it to your specialist. If your GP sent you for the test, the results will be sent to the GP clinic.

You will need an appointment with your specialist or GP to discuss the test results and how they might affect your treatment. Usually, your specialist will discuss your results and plan your subsequent care.

All these tests will give the specialist more information about the cancer such as where it is, if it is growing, and if it has spread. This is called staging. Staging helps to work out the best treatment plan for you.

Anal cancer stages | Ngā tūātupu o te mate pukupuku kōtore

You may have heard people talk about the stages of cancer. Staging provides an indication of the size of the cancer and if it has spread to other areas of the body and contributes to the treatment planning.

There are two ways in which the stage of cancer can be described. One uses numbers (stage 1, 2 etc) and the other uses letters and numbers (T1, N0 M0 etc) also known as TNM (Tumour-Nodes-Metastases) staging. The cancer may be described in one or both ways by your healthcare team.

Click here to learn more about the stages of cancer | Pāwhirihia kia whai mōhiotanga mō ngā tūātupu mate pukupuku.

TNM (Tumour-Nodes-Metastases) staging | Te Anga Tūātupu Pukupuku, Tīpona, Hora-mate

The TNM gives a number according to tumour size (T), how many lymph nodes are affected (N), and how far the cancer has spread, or metastasised, to distant parts of the body (M). This may be expressed as, for example, T1, N0, M0. This information is used to help decide the best treatment.

Tis | The lining of the anus may have abnormal cells |

T1 | The cancer is less than 2cm in size |

T2 | The cancer is between 2cm and 5cm in size |

T3 | The cancer is bigger than 5cm in size |

T4 | The cancer has moved into nearby organs irrespective of size |

N0 | No cancer cells are present in lymph nodes |

N1 | Cancer cells are present in nearby lymph nodes

|

M0 | The cancer has not spread to other parts of the body |

M1 | The cancer has spread to other parts of the body |

Staging using numbers | Te anga tūātupu mahinga tau

AIN | SIL | AIN (anal intraepithelial neoplasia) is also sometimes called SILS (anal squamous intraepithelial lesions). There are abnormal cells in the lining of the anus, but they are not cancerous. Depending on how the cells look under a microscope will help to determine if they are likely to turn cancerous or not. | |

Stage 1 | The cancer has not spread to any nearby tissue, lymph nodes or organs | |

Stage 2 | 2A

2B

| |

Stage 3 | 3A

3B

3C

| |

Stage 4 | Also called advanced cancer. The cancer has spread to other parts of the body and may or may not have spread to lymph nodes |

Prognosis (Life expectancy) | Matapaenga (Te wā ora)

Like any cancer there are many things that can impact on survival rates, so it is best to talk to your cancer specialist for guidance about your own care and outcomes. Remember, even with a diagnosis, no one can know for certain how long anyone will live. Estimates of life expectancy are based on historical data, however treatments are becoming more effective over time which changes these estimates.

Prognosis is usually improved the earlier the cancer is detected. Your doctor will be able to give you the best idea of prognosis.

Often, statistics talk about survival rates which are taken from an average of other patients. These are usually described in 1, 5 and 10-year survival rates. A 10-year survival rate is the proportion (or percent) of people who have not died 10 years after having cancer, however many people live much longer than this.

Click here to view anal cancer statistics related to morbidity (number of diagnoses) and mortality (survival rate) | Pāwhirihia kia tirohia ngā tauanga tahumaero me te matenga ā te Mate pukupuku kōtore. Remember that everyone is different, and statistics are only a guide.

Seeking a second opinion | E rapu ana i te whakaaro kē atu

Following diagnosis, some people choose to request a second opinion because they want to have peace of mind that they have explored all options and opinions available to them before starting treatment.

If you would like to know more about your care team and how to seek a second opinion, click here.

Treatment

Ngā momo rongoā

Treatment Options | Ngā kōwhiringa rongoā

There are a number of treatment options available, and it may feel confusing and unsettling not knowing which will be the best for you.

Treatment of anal cancer depends on its location, the stage of the cancer (how advanced it is at the time of diagnosis), and whether the person is otherwise medically fit.

The choice of treatments will be discussed with you and your whānau and your preferences will be considered. Your treatment will be discussed by a multidisciplinary team (MDT), which means that experts in different areas of cancer treatment (e.g., surgeons, gastroenterologists, radiologists, oncologists, and nurses) come together to share their expertise in order to provide the best patient care.

It is also important to note that more than one treatment may be needed to get the best results.

Treatment success rates are usually quite high for anal cancer, especially if diagnosed early. The usual treatment options are surgery, radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy.

See below to read more about the treatment options.

*Not all the options below will be applicable to everyone's situation. Some treatments listed may not be funded and would require the patient to pay directly. It is important to discuss all your options with your specialist team.

Surgery | Poka tinana

Surgery involves removing the cancer and some of the healthy tissue around the cancer.

There are two types of surgery for anal cancer.

Abdominoperineal resection

For patients with a cancer is inside the anal canal an abdominoperineal resection (APR) may be required. The rectum and anus are removed using incisions in the abdomen and around the anus. The cut end of the bowel is then brought through the muscle of the abdomen and sutured to the skin to form a stoma.

This type of stoma is called a colostomy. The bowel motion will pass into a stoma bag stuck to the skin of the abdomen. The stoma formed during an abdominoperineal resection is permanent. A stomal therapist will show you how to clean and take care of the stoma.

Local resection

A local resection removes the tumour with a small amount of normal tissue around it. This can be an option for some patients with cancer on the skin outside the anus (perianal cancer).The muscles around the anus are not normally affected and you will be able to pass stool out of the body as normal.

Chemotherapy | Haumanu matū

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells and stop the cancer growing and dividing.

Chemotherapy is a drug which is administered either by swallowing tablets; through an injection; or through infusion which is a small tube that is inserted into a vein. The drug works by moving through the blood stream to kill the cancer cells. Unfortunately, some healthy cells can also be harmed leading to side effects. Chemotherapy can be given alone or in combination with other therapies such as targeted therapy, surgery, or radiation. It is usually administered in an outpatient clinic and sometimes a hospital stay is needed if the doctor wants to monitor you following treatment.

Click here to view an example of chemotherapy infusion | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei kia tirohia te hoahoa whāuru haumanu matū.

Radiation therapy | Haumanu iraruke

Radiation therapy uses x-rays (ionising radiation) to damage the deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA) of cancerous cells to kill the cancer cells and stop the cancer growing.

Radiation therapy may be used in conjunction with surgery and/or chemotherapy.

Radiation can be delivered in two ways:

externally - External beam radiation

internally – Brachytherapy.

External beam radiation therapy | Haumanu Iraruke pūhihi rāwaho

Getting radiation therapy is similar to getting an X-Ray but the radiation is stronger. It is a painless procedure which involves lying on a table and a large machine rotating around you. It is directed at the tumour to try to kill the tumour or stop the cancer cells growing without damaging the healthy tissue nearby. Radiotherapy is usually performed in an outpatient clinic. It usually takes place everyday Monday to Friday and lasts for about 10-20 minutes. Your treatment team will be able to tell you how many weeks you will need radiotherapy for.

Click here to view an example of external beam radiation therapy.

Brachytherapy (Internal radiation therapy) | Haumanu Iraruke rāroto

Brachytherapy is not as commonly used as external beam radiotherapy but may be used as an addtional way of administering additional radiation in combination with external beam radiotherapy.

In Bracytherapy, radiation is placed inside the body near to the cancer site to kill the tumour or stop the tumour growing. The radioactivity only affects tissue that is very close to the implant. This means the tumour is treated, but healthy areas around it get much less radiotherapy. Areas of the body that are further away are not affected at all.

Clinical trials | Whakamātau haumanu

You may be eligible to take part in a clinical trial, which is a type of research study that investigates new or specialised therapies or treatments. While you are discussing therapy options with your care team, it is a good idea to ask about clinical trials that may be suitable for your condition and discuss whether participating may be right for you.

Being involved in a clinical trial may be beneficial in that you may access the latest treatments before they become generally available. Additionally, clinical trial participation is often associated with closer monitoring of your care and condition and potentially improved outcomes.

Clinical trials are free, and travel and accommodation (if needed) are provided.

Click here to learn more about clinical trials | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei kia tirohia tētahi tauira o te whāuru haumanu matū.

Palliative care | Pairuri

A specialist may refer a patient to palliative care services, but this doesn’t always mean end-of-life care. Today people can be referred to these services much earlier if they’re living with cancer. Palliative care can help one to live as well as possible including managing pain and symptoms. This care may be at home, in a hospital or at another location one prefers. Additional supportive care (treatment or services that support you through a cancer experience) are also available.

Traditional Māori Healing | Rongoā Māori

Rongoā Māori is a body of knowledge that takes a holistic view to wellbeing and treatment. In particular, it focuses on hinengaro (mind), wairua (soul), mauri (life essence), ngā atua (Gods) and te taiao (the environment).

There are many providers who are able to provide rongoā services. Your Māori Health team at the hospital will be able to connect you with one nearest to where you live.

See the below websites for more information on rongoā Māori

Other complementary therapies

Complementary therapies are treatments that are used alongside standard treatments. They are often used to boost the immune system, relieve symptoms, and enhance the effectiveness of standard treatments.

Speak to your doctor if you intend to use complementary therapies to ensure that they will work well alongside your treatment.

Some examples of complementary therapies are:

acupuncture

meditation and mindfulness

music therapy

massage

aromatherapy

naturopathy

tai chi

pilates

visualisation or Guided Imagery

spirituality.

Click here to find out more about complementary therapies

Side Effects from Treatment

Ngā mate āpiti

Side effects of anal cancer treatment | Ngā mate āpiti o te rongoā mate pukupuku kōtore

As with any medical treatment, you may experience side effects from your cancer treatment. This is perfectly normal and can be a sign that the treatment is working, although it may feel unpleasant. Side effects vary from person to person and depend on the type of treatment, the part of the body treated, and the length and dose of treatment. Most side effects are temporary and go away after treatment ends. Below you can find information on some common side effects of treatments and how you can manage them to improve your daily well-being.

You may experience side effects other than those discussed here.

If you experience side effects, let your healthcare team know when you next see them. If the symptoms feel extreme or are worrying you, get in contact with your oncology team sooner.

Common side effects of anal cancer treatments | Ngā mate āpiti tōkau o te rongoā mate pukupuku kōtore

Click on each treatment to learn more about the side effects of that treatment | Pāwhirihia i ia momo rongoā kia tirohia i ngā mate āpiti e hāngai ana

Surgery | Tipoka

The side effects of surgery depend on the type of surgery you have had, and your level of health before the operation. Your surgeon will discuss the risks associated with your cancer surgery. Feel free to ask questions to make sure you have all the information you need.

Local resection

Following local resection most people will feel some pain, but this is usually controlled with medication.

Abdominoperineal resection

Abdominoperineal surgery is major surgery and may cause more long-lasting side effects such as scarring in the abdomen, which can cause pain as food moves through the digestive system.

This type of surgery also carries a risk of damaging the urethra (where urine passes out of the body) which can cause problems urinating.

For men, the surgery also carries the risk of damaging the nerves to the penis leading to difficulties having an erection or orgasm.

For women, intercourse may be painful if there is significant scarring.

Some other side effects of surgery are due to the anaesthesia and should fade shortly after the surgery. These include:

nausea | whakapairuaki

vomiting | ruaki

dizziness | takaānini

agitation | kakare

Other side effects are due to the surgical procedure itself which should subside shortly after surgery. These include:

fatigue | ruha

pain at the site of the surgery | mamae ki te wāhi poka

Some additional side effects may present due to the disruption to your digestive system as a result of the surgery and could take weeks or months to recover from. These include:

diarrhoea and malabsorption | kotere

weight loss | heke taumaha

loss of appetite | minangaro

Chemotherapy and biological therapies | Ngā rongoā haumanu matū, koiora

Chemotherapy treatment kills cancer cells, but in the process, damages normal healthy cells which causes side effects. These side effects vary from person to person and depend on the type of treatment, the part of the body treated, and the length and dose of treatment. Below are some common side effects of this.

nausea and vomiting

loss of appetite

feeling full quickly

diarrhoea and constipation

fatigue

weight loss

sore mouth or throat

taste changes

foggy brain.

Some chemotherapy side effects can be life threatening therefore it is important to go to contact your oncology team or go to your nearest emergency department immediately if you experience any of the following and let them know that you are undergoing chemotherapy treatment. These include:

fever or chills

pain in your chest or difficulty breathing

diarrhoea

vomiting that is not eased with anti-sickness medication

bleeding from the gums or nose that doesn’t stop

pain or blood present when passing urine.

Radiation therapy | Haumanu iraruke

Radiation therapy is used to kill cancer cells, but it can also kill some healthy cells near to the cancer site too.

Radiation therapy is used to kill cancer cells, but it can also kill some healthy cells near to the cancer site too. Although radiation therapy itself does not hurt, you may experience some symptoms afterwards due to the affect the radiation has on the healthy cells. These symptoms may include:

fatigue | ruha

diarrhoea and constipation | kotere & kōreke

swelling & bleeding | te Pupuhi & totorere – due to damage to the blood cells lining the inside of the anus causing swelling and bleeding, or scarring on the inside wall of the anus, which can affect bowel movements.

hair loss | rutu makawe

similar to a sunburn at the radiation site | mamae Tīkākā

sexual and/or fertility complications | turingonge taihema – For women, radiation may also cause the vagina to become narrower and shorter and in men can cause erectile disfunction or impotence.

Often the side effects of radiation therapy are not long lasting and fade once radiation therapy stops.

Additionally, radiation therapy can cause fertility problems in both men and women and so sperm banking or egg freezing may be a consideration.

For women, radiation may also cause the vagina to become narrower and shorter and in men can cause erectile disfunction or impotence.

Managing symptoms and side effects | Whakahaere tohumate me ngā mate āpiti

Click on the symptoms below to find information on how to manage symptoms and side effects | Pāwhirihia i ia momo tohumate mō ngā mōhiohio kia whakahaere ai ngā tohumate me ngā mate āpiti

Fatigue | Ruha

A common side effect of treatment is feeling constant tiredness (fatigue). Treatment or the cancer itself can reduce the number of red blood cells in your body, resulting in anaemia, which can make you feel very tired.

Tips to manage fatigue | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere i te ruha:

Use your energy wisely

plan ahead for when you feel too tired to cook

shop online for groceries

bulk cook meals you can store in the freezer

cook when you have more energy

ask and accept offers of help with shopping and cooking from whānau and friends

use home delivery services such as Meals on Wheels or other companies that bring pre-prepared food to you. You can ask for help to access these via your social worker

keep snacks handy in your bag or car.

Activity can help with fatigue

regular, gentle exercise can help improve fatigue and your appetite

activity can mean many things – walking, stretching, even vacuuming!

set small goals. Set a timer for five minutes and see what you can manage in this time

eat with others.

Loss of appetite | Kore hiakai

It can be discouraging to lose your appetite. You may lose your appetite because of the effects of cancer itself, the treatment, or other side effects, such as feeling sick, not enjoying the smell of food, or feeling upset. To help you can:

eat small amounts often, e.g., every 2–3 hours. Keeping to a regular eating pattern rather than waiting until you are hungry will mean your body gets the nourishment it needs to

use a smaller plate – a big plate of food may put you off

eat what you feel like when you feel like it. Have cereal for dinner or a main meal at lunch

include a variety of foods in your diet

sip fluids throughout the day

replace water, tea and coffee with drinks or soups that add energy (kilojoules/calories), such as milk, milkshake, smoothies, replacement drinks or soup

relax dietary restrictions – maintaining your weight or regaining weight you have lost is more important than avoiding full-fat and other high-energy foods

gentle physical activity can stimulate appetite – take a short walk around the block

eat with others

keep snacks handy e.g., in your bag or car so you can eat on the go

talk to your dietitian about liquid meal replacements that might be easier to digest.

Taste or smell changes | Rongo kakara me te hā

Some treatments such as chemotherapy can change the way food and/or drink taste or smell. It may taste bland or metallic.

Tips on managing changes in taste include:

add extra flavour to food if it tastes bland – like fresh herbs, lemon, lime, ginger, garlic, soy sauce, honey, chilli, or pepper

experiment with different food, as your tastes may change

if meat tastes bad during treatment, replace it with other protein sources like cheese, eggs, nuts, dairy foods, baked beans, lentils, or chickpeas

add small amounts of sugar to food if it tastes bitter or salty

use a straw when drinking

change from using metal cutlery to plastic or bamboo cutlery.

Tips on managing changes in smell include | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere i ngā panoni rongo kakara:

eat cold food or food at room temperature (hot food smells more)

reheat pre-prepared meals in the microwave so the cooking smell doesn’t put you off

stay out of the kitchen, if possible, when food is being prepared

ask family or friends to cook

use the exhaust fan, open the kitchen window, or cook outside to help reduce cooking smells.

Nausea and vomiting | Whakapairuaki me te ruaki

Feeling sick and vomiting are often side effects of cancer, its treatment, or some medicines. They often occur together, but not always.

Nausea | Whakapairuaki

Nausea is stomach discomfort and the sensation of wanting to vomit. Nausea can be a precursor to vomiting the contents of the stomach and may be caused by treatment, stress, food odours, gas in the gastrointestinal tract, motion sickness or even the thought of having treatment.

Tips on how to cope with nausea | Ngā kupu āwhina ki te morimori i te whakapairuaki:

have a light snack before treatment and wait a few hours before eating again

eat small meals 5–6 times during the day. Going without food for long periods can make nausea worse

snack on dry or bland foods, e.g., crackers, toast, dry cereals, bread sticks or pretzels

choose cold foods or foods at room temperature instead of hot, fried, greasy, or spicy foods

eat and drink slowly and chew your food well

try foods with ginger, e.g., ginger biscuits, or ginger beer

avoid foods that are overly sweet, fatty, fried, spicy, or oily, or that have strong smells

brush teeth regularly to help reduce unpleasant tastes that may make you feel nauseated

do not eat your favourite food when feeling nauseated to avoid developing a permanent dislike

suck on hard lollies – flavoured with ginger, peppermint, or lemon

try ginger food and drink items, such as candied ginger, ginger beer, ginger ale, or ginger tea. Talk to your dietitian doctor or pharmacist about ginger supplements

take anti-nausea medicines as prescribed. Let the doctor know if the medicines don’t seem to be working.

Vomiting | Ruaki

Vomiting is the forcible emptying (“throwing up”) of stomach contents through the mouth. Vomiting can follow nausea and may be caused by treatment, stress, food odours, gas in the gastrointestinal tract, motion sickness or even the thought of having treatment.

Vomiting is more serious than nausea. Vomiting can cause dehydration and increase the risk of malnutrition. See a doctor if you are vomiting for more than one day, especially if you cannot keep water down as you may become dehydrated.

Tips on how to cope with vomiting | Ngā kupu āwhina ki te morimori i te ruaki:

Take small sips of water or clear liquids, such as ginger ale, soda water or sports drinks like Gatorade or Hydrolyte. Dilute sweet drinks. If you feel like a fizzy drink, open it, and let it sit for 10 minutes or so, and drink it when it’s a bit flat

sucking on crushed ice cubes or an ice block can be soothing

once you can keep clear liquids down try some different drinks, such as consommé and clear broths, weak tea, herbal tea, fruit drinks, beef, and chicken stocks

have small, frequent meals and snacks throughout the day

introduce bland, starchy foods, such as plain biscuits, bread or toast with honey or jam, peanut butter, rice, yoghurt, or fruit. Attempt small, frequent servings at first

consume a little bit more each time until you are eating a well-balanced diet.

Chewing and swallowing | Ngaungau me te horomi

After treatment chewing and swallowing may be difficult and painful. Surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy can cause temporary problems. People with dentures who have lost weight may also find their teeth become loose, which can make eating difficult.

Signs that you are having problems with chewing and swallowing include taking longer to chew and swallow, coughing or choking while eating or drinking, or food sticking in your mouth or throat like a ball.

Tips on chewing and swallowing | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te ngaungau me te horomi:

change how you prepare your food by chopping food up into smaller pieces or pureeing

let your doctor know that you are having issues and get a referral to see a speech pathologist and dietitian

a speech pathologist can monitor your ability to swallow and suggest modifications to the texture of your food once your ability to swallow and chew begins to improve. A dietitian can ensure you are meeting your nutritional needs.

Mouth changes | Ngā panonitanga o te waha

Some chemotherapy drugs and some pain medicines can make your mouth dry, cause mouth ulcers, or change the amount of saliva in your mouth. A dry mouth can increase the risk of tooth decay and infections such as oral thrush, which will make eating harder.

Ulcers may also be present in your digestive tract, causing discomfort in the stomach or bowel and diarrhoea.

Tips to lessen discomfort with mouth sores | Ngā kupu āwhina ki te whakamauru i ngā harehare waha:

suck on ice cubes

eat soft foods – stews, soups, scrambled eggs, and smoothies

cold foods and fluids may be more comfortable than hot ones

avoid ‘coarse’ foods that can irritate your mouth, such as crackers, toast, nuts, and seeds

avoid spicy or very hot foods

use a straw and direct liquids away from the areas where mouth sores are most painful

talk to your doctor about medication or mouth washes to help manage the pain and allow you to eat more comfortably.

Tips to relieve a dry mouth | Ngā kupu āwhina ki te whakamauru i te waha maroke:

suck on ice cubes

keep your mouth clean with regular mouthwashes to prevent infections

gargle with 1⁄2 tsp salt or 1 tsp bicarbonate of soda in a glass of water

choose an alcohol-free mouthwash to avoid irritating your mouth further

use a soft toothbrush when cleaning your teeth

ask your dentist or health care team about suitable mouth rinses or oral lubricants

limit alcohol and coffee as these are dehydrating fluids and avoid smoking

avoid ‘coarse’ foods that can irritate your mouth, such as crackers, toast, nuts, and seeds

avoid spicy or very hot foods

soften food by dipping it into milk, soup, tea, or coffee

moisten with sauce, gravy, cream, custard

sip fluids with meals and throughout the day

chew sugar-free gum to stimulate the flow of saliva.

Changes in bowels- constipation and diarrhoea | Ngā panonitanga o ngā kōpiro

Living with cancer and its treatments can result in changes to your bowel habits. This could be differences in the appearance, consistency, and/or the smell of your stools.

Constipation | Kōroke

This is when your bowel motions are infrequent and difficult to pass. It can be caused by different factors including regularly taking opioid medicines; having a diet low in fibre; not getting enough exercise; not having enough fluids to drink (dehydration); or having a low overall food intake.

Tips on how to manage constipation | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere kōroke:

soften stools by drinking 8–10 glasses of fluid a day, e.g., water, herbal tea, milk-based drinks, soup, prune juice

eat foods high in fibre, e.g., wholegrain breads, cereals, or pasta; raw and unpeeled fruits and vegetables; nuts and seeds; legumes and pulses

if you are increasing the amount of fibre in your diet, increase fluids to prevent the extra fibre making constipation worse

ask your doctor about using a laxative, stool softener and/or fibre supplement

exercise – check with your doctor, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist about the amount and type of exercise that is right for you.

Diarrhoea | Kotere

This means your bowel motions are watery, urgent, and frequent. You may also get abdominal cramping, wind, and pain. Frequent loose stools can occur because you are not digesting food or absorbing nutrients properly. Cancer treatment, medicines, infections, reactions to certain foods and anxiety can all cause diarrhoea.

Diarrhoea can result in dehydration, so it’s important to stay hydrated by drinking extra fluids. Every time you have a loose bowel movement you should drink an extra cup of non-caffeinated fluid. If you have diarrhoea for several days, see your doctor so he/she can determine the cause and help to manage your diarrhoea. Your doctor may decide to prescribe you anti-diarrhoea or over-the-counter medication.

Tips on how to manage diarrhoea | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere kōtere:

drink plenty of fluids to avoid becoming dehydrated. Water and diluted cordials are better than high-sugar drinks, alcohol, or caffeinated fluids – remember signs of dehydration are smaller amounts of dark urine

choose low-fibre foods, e.g., bananas, mashed potato, rice, pasta, white bread, oats, steamed chicken without the skin, white fish

avoid foods that increase bowel activity, e.g., spicy, fatty, or oily foods, caffeine, alcohol, or artificial sweeteners

try soy milk or lactose-free milk if you develop a temporary intolerance to milk (lactose)

don’t eat too many raw fruit and vegetable skins and wholegrain cereals as they may make diarrhoea worse

avoid foods and drinks that are high in sugar, such as cordial, soft drinks and lollies

avoid foods sweetened with artificial sweeteners such as sorbitol, mannitol, and xylitol. These are often marketed as ‘sugar-free’

it may also help to eat small, frequent meals throughout the day, rather than three large meals.

Heartburn (Indigestion) | Tokopā

Some cancers and treatments can cause heartburn, which is a burning sensation in the upper chest, oesophagus and/or throat. It is caused by the contents of the stomach coming back up into the oesophagus (reflux).

Heartburn may make you feel too uncomfortable to eat much, which could lead to weight loss. If the tips below do not relieve heartburn, let your doctor know as medication may help to prevent or manage these side effects.

Tips to manage heartburn | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere tokopā:

avoid large meals; try to eat 3 small meals and 3 small snacks throughout the day

eat slowly and take the time to enjoy your meal

avoid wearing tight clothing while eating, especially belts

sip fluids between meals, rather than drinking large amounts at mealtimes

limit or avoid foods that may make heartburn worse, e.g., chocolate, highly seasoned spicy foods, high-fat foods (e.g., fried food, pastries, cream, butter, and oils), tomato and tomato products, citrus fruits, coffee (including decaf), strong tea, soft drinks, and alcohol

straight after eating, sit upright for at least 30 minutes and avoid lying down or activities that involve bending over (e.g., gardening).

Peripheral neuropathy | Pūtau Iotaiaki mōwaho

Peripheral neuropathy is caused by damage to the peripheral nerves. These are the nerves in the body outside the brain or spinal cord. Peripheral neuropathy may be caused by cancer, cancer treatments or other health problems. It most commonly affects the hands and feet. Peripheral neuropathy caused by cancer treatment will get better over time with proper treatment and care.

The most common symptoms of peripheral neuropathy can include | Ngā kōrero tōkau mō te Pūtau Iotaiaki Mōwaho:

tingling, burning, numbness or pain in the hands or feet

difficulty doing up buttons and picking up small items

loss of feeling especially in the hands and feet

problems with balance or walking, and clumsiness

be safe. If you notice changes in your walking, stance, fine and gross motor skills, or balance speak to your doctor as soon as possible and ask for a referral to an occupational therapist, exercise physiologist or physiotherapist

Tips to manage peripheral neuropathy | Ngā kupu āwhina mō te whakahaere Pūtau Iotaiaki Mōwaho:

use a night light so that you don’t trip or bang into anything if you need to go to the toilet at night

keep clutter and rugs off the floors

have clear paths to the toilet and bedroom

use handrails where possible

use nonslip mats in the shower and bathroom

be careful on slippery and wet floors

do not walk around bare footed as you may not notice if you stand on something that could damage your feet

wear shoes and slippers that fit well

use a walking stick if you need to

wear gloves when washing up, cleaning and gardening

test water temperature with your elbow

take care when cutting food and opening cans or jars

keep your skin moisturised to prevent cracking

check your hands and feet daily for signs of injury, rubbing, redness or infection

ask for help if you need it, e.g., to do up buttons and shoes

find clothes and shoes that are easy to put on and take off

avoid driving if symptoms are severe.

Alerting your healthcare team of side effects | Whakaohititia tō rōpu tiaki hauora ki ngā mate āpiti

Your health care team wants to hear about your side effects. Your questions and concerns are important. Do not be afraid to share them. Ask your health care team who you should contact if you feel that your side effects need assessing right away.

Treatment changes | Ngā pānonitanga maimoa

Occasionally, if you have severe side effects, your doctor may discuss delaying or changing your treatment to prevent further discomfort.

Start a symptom diary | Tīmatahia he rātaka tohumate

Keeping track of your symptoms can help you and your cancer care team to manage them better.

Know who to contact if you have a problem | Me mōhio hoki ki te whakapā atu ki a wai mēnā he raru tāu

Ask your doctor or nurse:

when you should call for help or advice

who you should contact

how to contact them (including at night or weekends).

Keep this information where you can easily find it.

Diet & Nutrition

Whiringa kai me te taioranga

Why is diet and nutrition important? | He aha e whaitikanga ai te whiringa kai me te taioranga?

You may be feeling that some things are out of your control, however there are a number of actions that you can take to make sure your body is in the best condition to cope with, and heal from, the symptoms and side effects of the cancer and cancer treatments.

Below you will find detail about why diet and nutrition can make a big difference to the healing process and how you feel.

Why does anal cancer affect nutrition? | He aha e pāngia ai te mate pukupuku kōtore i te taioranga?

Anal cancer, and cancer treatments place extra demands on your body. They can also cause you to lose your appetite and energy, putting you at an increased risk of malnutrition. It is important to ensure that your body is receiving the right nutrition before, during and after treatment to be able to cope with these extra demands.

Your food choices when you have cancer and are undergoing treatment may be very different from what you are used to eating.

The main goal is to try to keep your weight constant, maintain muscle strength, maintain a healthy weight, and have more energy, all of which help your body to heal properly, improve your quality of life and give you the energy to cope with all the new challenges treatment may bring.

Anal cancer and the treatments for anal cancer may impact | Ka pāngia pea te mate pukupuku kōtore me ngā rongoā:

your nutritional requirements and what you need to eat

how much you eat

your appetite

your ability to digest food

your ability to maintain your weight and muscle mass

your energy levels and general wellbeing.

Good nutrition can help to | E āwhina ai te taioranga pai ki te:

manage the side effects of treatment

speed up recovery after treatment

heal wounds and rebuild damaged tissues after surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or other treatment

improve your body’s immune system and ability to fight infections.

Overall, try to make food choices that provide you enough | Heoi, kia whakamātau koe ki te whiriwhiri i ngā kai e ratoa ai:

calories (to maintain your weight)

protein (to help rebuild tissues that cancer treatment may harm)

nutrients such as vitamins and minerals

fluids (essential for your body’s functioning).

Exercise can also help with appetite and digestion issues related to treatment.

Nutritional tips during treatment | He kupu āwhina taioranga e koke ai te maimoatanga

Click here to learn more about nutritional tips during treatment | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei mō ētahi atu whakamōhiotanga

To maintain good nutrition:

you may need more energy (kilojoules/calories)

eat small, frequent meals or snacks, rather than three large meals a day

ask for a referral to a dietitian – discuss eating issues, weight issues, muscle loss

do some light physical activity, such as walking, to improve appetite and mood, reduce fatigue, help digestion, and prevent constipation

check with your doctor or dietitian before taking vitamin or mineral supplements or making other changes to your diet

relax dietary restrictions, e.g., choose full-cream rather than low-fat milk

consider using nutritional supplements if you cannot eat enough – discuss options with your doctor, palliative care specialist or dietitian.

Nutritional tips following surgery | Ngā kōrero āwhina taioranga whai muri i te pokanga

Click here to learn more about nutritional tips following surgery | Pāwhirihia ki kōnei mō ētahi atu whakamōhiotanga

Surgeries used to treat cancer may result in a variety of side effects, including weight loss. The side effects usually only last for a short period of time, but you may have to make some changes to your diet to ensure that you are getting enough nutrition and maintaining your weight.

Your body needs good nutrition after surgery, and it is an important part of your recovery process. If you are struggling to eat or drink, the hospital may prescribe nutrition supplements, or recommend tube feeding, to help you to maintain weight and provide you with the nutrients you need for speedy recovery.

Tips on maintaining weight after surgery | Kupu āwhina kia ū te taumaha whai muri i te pokanga:

monitor your weight – weigh yourself once or twice a week to monitor for any weight loss.

if you are losing weight, tell your doctor and get a referral to see a dietitian.

eat small, frequent meals after surgery so your digestive system only has to deal with a small amount of food at a time.

We recognise that dietary changes have a huge impact on everyone with cancer. It can take a while to get used to changes to your diet and lifestyle but finding ways to manage your diet and symptoms can help you feel more in control. It can also be helpful to speak to your dietitian, doctor or nurse.

Living well with cancer

Kia ora pai ai

Learn more about living with cancer.

Read about other people’s cancer journeys see our personal journeys page.